I went to the Phoenix Art Museum sometime ago with my photo club. The curator of the Norton Gallery (Becky Zenf) presented a lecture (Debating Modern Photography: The Triumph of Group f/64) on the classic works by amazing photographers such as Ansel Adams and Edward Weston. What I was truly thrilled about was how synchronistic her lecture was with regard to my own personal study on the History of Photography.

I had been reading a book on the works of Edward Weston some weeks ago and in it were personal letters where he discusses at length his disdain for Pictorial photography and for this art movement in general. Being curious, I knew immediately I had to learn everything I could about this movement and its impact on modern photography. I wasn't disappointed in my research either.

The Pictorial Movement

To summarize as best as I can, the Pictorial Movement was initially born out of a recurring need to defend, justify and validate photography as a legitimate art form. We think little these days about whether photography is or is not an art form. Of course, it is! We accept this idea in today's modern world as being conspicuously self-evident. However, it certainly wasn't always this way.There was once a tremendous battle within the arts in general. Sides were taken and critical and judgmental bombs were lobbed at each other. And there were enormous struggles in this battle for the photographers who constantly faced insurmountable obstacles from artistic biases and “norms” of the populous right from the very start. Heroes and legends emerged from this battle (unsung though they were) who profoundly altered the way people viewed photography.

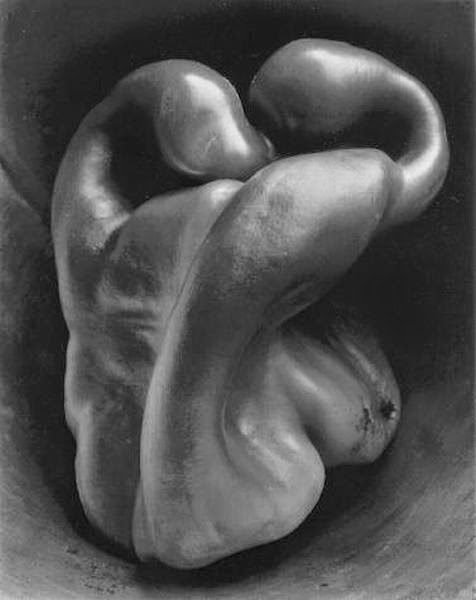

|

| Pepper No. 30 (1930) by Weston |

Photography was initially seen as a trivial parlor trick and later as (perhaps a legitimate form of) journaling or an archival documentation of events through its ability to capture reality with great fidelity. Prior to the discoveries of the processes of photography, there was only one way to record an event pictorially and that was through the stylus of an artist.

Mind you, none of the arts had ever promised to tell the truth about an event. Indeed, ancient and modern history is replete with distorted and “conceptualized” recordings (art) of past people and events. And the level of distortion shifts from culture to culture in terms of what was to be glorified about our “celebrities” and the major events of the period. The artistic representations were simply manifestations of an artist's perspective (born out of culture and environment), imagination and skill.

Discrepancies from Reality

The audiences of art (then as now) when viewing a work of art, accept (both consciously and unconsciously) the blatant discrepancies from reality that may be portrayed. These are seen as “artistic license” or the “artist's interpretation” of the person or event. No one typically calls a painting a “fraud” (as they incessantly do these day with photography) because it has long been understood and accepted that the artistic work is an expression of the artist and certainly not a true and faithful rendering of reality. Not so much for photographers; they were expected and even bullied to rigorously report, document or journal reality.“The Camera Never Lies”

So, just imagine if you will, how artists and art-lovers alike felt about photography when it came along as the new kid on the block. Though none were calling attention to it as such, there was a deep sense of threat that photography posed to the artistic empire that had stood stalwart for millennia.As you might imagine, artists and their benefactors were all threatened by this new invention which could faithfully record an event with even greater fidelity than they could. Statements such as “the camera never lies” were propagated during this time and may have been more of a ploy to anchor a lack of artistic value in photography than champion it's virtues. Mind you, this statement in itself was another monumental lie that would be exposed through the photographic trickery of the spiritualist of the late 1800s.

|

Taken September, 1936 by Captain Provand and

Indre Shira, two photographers who were assigned to photograph Raynham Hall for Country Life magazine. |

Because so many believed that the camera couldn't lie it was easy for charlatans to manufacture captured ghosts on film with something as simple as a double exposure. Of course, the average person of the time didn't know or understand the technicalities that went into the processing of photographic images. And it is, perhaps, due in large part to this trickery that many people later (as now) look at photographs with a critical and skeptical eye. “Is this real?”

The trouble with this perspective is that even though the camera is amazing in the way it can capture crisp details and freeze moments of time, no one in reality ever actually sees reality this way. For humans (and every living creature on earth) we actually see life as a constant, fluid stream of time intervals. And each of us have our own unique perspective of how we perceive what it is that we see with our own eyes.

As an example, you may look at the one you love and either ignore, overlook or be essentially blind to their facial flaws, blemishes or physical shortcomings. This is because we don't only “see” with our eyes. We see with our hearts and minds too. Yet, the camera captures every embarrassing and minute detail for all the world to see. And this is only the tip of the proverbial iceberg when it comes to the camera “lying” about reality.

As wonderful and amazing as the technology of photography may be (and continues to improve upon), it has it glaring limitations. By that I mean that the camera is limited by technical things like light capacity, film or sensor sensitivity, lens quality, operator competency, etc... These all play into what is the total gestalt of an image capture. And then there's the post processing, which these days means using Photoshop, and this too has it's limits and boundaries.

If the final objective is to capture what we see with our naked-eyes, then photography is still only providing us with very close facsimiles, yet still pales horribly in comparison to the millions of receptors of all our senses.

Soulless and Cold

Back to the history of photography, during the 1800s, painters collectively viewed photography with cynicism and contempt. In comparison to painting, it was considered “soulless and cold” in its absolute optical fidelity of a subject. The painter had long been heralded as the rightful interpreter of imagery and this new (fandangled) technology threatened to dismantle the very foundations of their livelihood. Many fretted, “Why would anyone want a painted portrait when they could simply have a photograph taken?” Certainly, it was more expedient and convenient than sitting for a portrait with a painter.The answer to this (at least to the painter) was because photography simply was not art! And, they reasoned, this was due of the initial lack of skill it took to open a camera shutter. Art for the painter, which required years of practice as well as innate skills, had a value that transcended visual reality. To the artist, “interpreting” a subject through painting was this “transcended value”. You can see by this that not only were photographers having to form justifications for their existence, but so were artists.

God Bless Soft-Focus

It was clear that photographers (and those impressed and appreciative of it) had a tough row to hoe if it was ever to be seen credibly as “art”. Initially, photographers were taking their queue from modern as well as classical painting in order to show that photography could indeed stand on an equal footing with painting on the merits of the visual impact of the image. This gave birth to what is called the “Pictorialism” in photography in which the imagery closely resembles painterly qualities. Soft-focus photography was honed during this period. |

| Anne Wardrope (Nott) Brigman (1908) |

Photographers such as Alfred Stieglitz had a profound impact on this movement and he is credited with moving photography towards the goal of photography being recognized as art in America, perhaps more than just about any other photographer.

The Group f/64

Edward Weston, who also had a profound effect on the photographic universe, began his career as an advocate of the Pictorial movement but later rejected it as a pitiful justification for what he believed should be universally accepted (without justification) as an art form; namely, fine art photography which naturally and unabashedly stands on its own. Weston was of these great photography heroes to be sure. He was also a great admirer of Stieglitz, yet later became one of the founding members of Group f/64 (whom also boasts artists such as Ansel Adams as a founder) which completely rejected Pictorialism.The more I study the subject, this question of whether photography is or is not an art form seems to be extraordinarily obtuse. I must agree with Weston that not only is photography “legitimately” an art-form, but it has been nothing more than this since it's very inception.

My journey to the Phoenix museum was both enlightening and self-affirming to what I have always known and have spent the greater part of my life enjoying. Namely, the “art” of photography. In today's visually media-driven life, photography is not just an after-thought, it is the central focus and pivotal nexus that unites all the arts. Yes, "we've come a long way, baby.”